9.3 Using Secrets to pass sensitive data to containers

In the previous section, you learned how to store configuration data in ConfigMap objects and make it available to the application via environment variables or files. You may think that you can also use config maps to also store sensitive data such as credentials and encryption keys, but this isn’t the best option. For any data that needs to be kept secure, Kubernetes provides another type of object - Secrets. They will be covered next.

9.3.1 Introducing Secrets

Secrets are remarkably similar to config maps. Just like config maps, they contain key-value pairs and can be used to inject environment variables and files into containers. So why do we need secrets at all?

Kubernetes supported secrets even before config maps were added. Originally, secrets were not user-friendly when it came to storing plain-text data. For this reason, config maps were then introduced. Over time, both the secrets and config maps evolved to support both types of values. The functions provided by these two types of object converged. If they were added now, they would certainly be introduced as a single object type. However, because they each evolved gradually, there are some differences between them.

Differences in fields between config maps and secrets

The structure of a secret is slightly different from that of a config map. The following table shows the fields in each of the two object types.

Table 9.3 Differences in the structure of secrets and config maps

| Secret | ConfigMap | Description |

|---|---|---|

| data | binaryData | A map of key-value pairs. The values are Base64-encoded strings. |

| stringData | data | A map of key-value pairs. The values are plain text strings. The stringData field in secrets is write-only. |

| immutable | immutable | A boolean value indicating whether the data stored in the object can be updated or not. |

| type | N/A | A string indicating the type of secret. Can be any string value, but several built-in types have special requirements. |

As you can see in the table, the data field in secrets corresponds to the binaryData field in config maps. It can contain binary values as Base64-encoded strings. The stringData field in secrets is equivalent to the data field in config maps and is used to store plain text values. This stringData field in secrets is write-only. You can use it to add plaintext values to the secret without having to encode them manually. When you read back the Secret object, any values you added to stringData will be included in the data field as Base64-encoded strings.

This is different from the behavior of the data and binaryData fields in config maps. Whatever key-value pair you add to one of these fields will remain in that field when you read the ConfigMap object back from the API.

Like config maps, secrets can be marked immutable by setting the immutable field to true.

Secrets have a field that config maps do not. The type field specifies the type of the secret and is mainly used for programmatic handling of the secret. You can set the type to any value you want, but there are several built-in types with specific semantics.

Understanding built-in secret types

When you create a secret and set its type to one of the built-in types, it must meet the requirements defined for that type, because they are used by various Kubernetes components that expect them to contain values in specific formats under specific keys. The following table explains the built-in secret types that exist at the time of writing this.

Table 9.4 Types of secrets

| Built-in secret type | Description |

|---|---|

| Opaque | This type of secret can contain secret data stored under arbitrary keys. If you create a secret with no type field, an Opaque secret is created. |

| bootstrap.kubernetes.io/token | This type of secret is used for tokens that are used when bootstrapping new cluster nodes. |

| kubernetes.io/basic-auth | This type of secret stores the credentials required for basic authentication. It must contain the username and password keys. |

| kubernetes.io/dockercfg | This type of secret stores the credentials required for accessing a Docker image registry. It must contain a key called .dockercfg, where the value is the contents of the ~/.dockercfg configuration file used by legacy versions of Docker. |

| kubernetes.io/dockerconfigjson | Like above, this type of secret stores the credentials for accessing a Docker registry, but uses the newer Docker configuration file format. The secret must contain a key called .dockerconfigjson. The value must be the contents of the ~/.docker/config.json file used by Docker. |

| kubernetes.io/service-account-token | This type of secret stores a token that identifies a Kubernetes service account. You'll learn about service accounts and this token in chapter 23. |

| kubernetes.io/ssh-auth | This type of secret stores the private key used for SSH authentication. The private key must be stored under the key ssh-privatekey in the secret. |

| kubernetes.io/tls | This type of secrets stores a TLS certificate and the associated private key. They must be stored in the secret under the key tls.crt and tls.key, respectively. |

Understanding how Kubernetes stores secrets and config maps

In addition to the small differences in the names of the fields supported by config maps or secrets, Kubernetes treats them differently. When it comes to secrets, you need to remember that they are handled in specific ways in all Kubernetes components to ensure their security. For example, Kubernetes ensures that the data in a secret is distributed only to the node that runs the pod that needs the secret. Also, secrets on the worker nodes themselves are always stored in memory and never written to physical storage. This makes it less likely that sensitive data will leak out.

For this reason, it’s important that you store sensitive data only in secrets and not config maps.

9.3.2 Creating a secret

In section 9.2, you used a config map to inject the configuration file into the Envoy sidecar container. In addition to the file, Envoy also requires a TLS certificate and private key. Because the key represents sensitive data, it should be stored in a secret.

In this section, you’ll create a secret to store the certificate and key, and project it into the container’s filesystem. With the config, certificate and key files all sourced from outside the container image, you can replace the custom kiada-ssl-proxy image with the generic envoyproxy/envoy image. This is a considerable improvement, as removing custom images from the system is always a good thing, since you no longer need to maintain them.

First, you’ll create the secret. The files for the certificate and private key are provided in the book’s code repository, but you can also create them yourself.

Creating a TLS secret

Like for config maps, kubectl also provides a command for creating different types of secrets. Since you are creating a secret that will be used by your own application rather than Kubernetes, it doesn’t matter whether the secret you create is of type Opaque or kubernetes.io/tls, as described in table 9.4. However, since you are creating a secret with a TLS certificate and a private key, you should use the built-in secret type kubernetes.io/tls to standardize things.

To create the secret, run the following command:

$ kubectl create secret tls kiada-tls \

--cert example-com.crt \

--key example-com.key

This command instructs kubectl to create a tls secret named kiada-tls. The certificate and private key are read from the file example-com.crt and example-com.key, respectively.

Creating a generic (opaque) secret

Alternatively, you could use kubectl to create a generic secret. The items in the resulting secret would be the same, the only difference would be its type. Here’s the command to create the secret:

$ kubectl create secret generic kiada-tls \

--from-file tls.crt=example-com.crt \

--from-file tls.key=example-com.key

In this case, kubectl creates a generic secret. The contents of the example-com.crt file are stored under the tls.crt key, while the contents of the example-com.key file are stored under tls.key.

NOTE

Like config maps, the maximum size of a secret is approximately 1MB.

Creating secrets from YAML manifests

The kubectl create secret command creates the secret directly in the cluster. Previously, you learned how to create a YAML manifest for a config map. What about secrets?

For obvious reasons, it’s not the best idea to create YAML manifests for your secrets and store them in your version control system, as you do with config maps. However, if you need to create a YAML manifest instead of creating the secret directly, you can again use the kubectl create --dry-run=client -o yaml trick.

Suppose you want to create a secret YAML manifest containing user credentials under the keys user and pass. You can use the following command to create the YAML manifest:

$ kubectl create secret generic my-credentials \

--from-literal user=my-username \

--from-literal pass=my-password \

--dry-run=client -o yaml

apiVersion: v1

data:

pass: bXktcGFzc3dvcmQ=

user: bXktdXNlcm5hbWU=

kind: Secret

metadata:

creationTimestamp: null

name: my-credentials

Creating the manifest using the kubectl create trick as shown here is much easier than creating it from scratch and manually entering the Base64-encoded credentials. Alternatively, you could avoid encoding the entries by using the stringData field as explained next.

Using the stringData field

Since not all sensitive data is in binary form, Kubernetes also allows you to specify plain text values in secrets by using stringData instead of the data field. The following listing shows how you’d create the same secret that you created in the previous example.

Listing 9.16 Adding plain text entries to a secret using the stringData field

apiVersion: v1

kind: Secret

stringData:

user: my-username

pass: my-password

The stringData field is write-only and can only be used to set values. If you create this secret and read it back with kubectl get -o yaml, the stringData field is no longer present. Instead, any entries you specified in it will be displayed in the data field as Base64-encoded values.

TIP

Since entries in a secret are always represented as Base64-encoded values, working with secrets (especially reading them) is not as human-friendly as working with config maps, so use config maps wherever possible. But never sacrifice security for the sake of comfort.

Okay, let’s return to the TLS secret you created earlier. Let’s use it in a pod.

9.3.3 Using secrets in containers

As explained earlier, you can use secrets in containers the same way you use config maps - you can use them to set environment variables or create files in the container’s filesystem. Let’s look at the latter first.

Using a secret volume to project secret entries into files

In one of the previous sections, you created a secret called kiada-tls. Now you will project the two entries it contains into files using a secret volume. A secret volume is analogous to the configMap volume used before, but points to a secret instead of a config map.

To project the TLS certificate and private key into the envoy container of the kiada-ssl pod, you need to define a new volume and a new volumeMount, as shown in the next listing.

Listing 9.17 Using a secret volume in a pod: pod.kiada-ssl.secret-volume.yaml

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: kiada-ssl

spec:

volumes:

- name: cert-and-key

secret:

secretName: kiada-tls

items:

- key: tls.crt

path: example-com.crt

- key: tls.key

path: example-com.key

mode: 0600

...

containers:

- name: kiada

...

- name: envoy

image: envoyproxy/envoy:v1.14.1

volumeMounts:

- name: cert-and-key

mountPath: /etc/certs

readOnly: true

...

ports:

...

If you’ve read section 9.2 on config maps, the definitions of the volume and volumeMount in this listing should be straightforward since they contain the same fields as you’d find if you were using a config map. The only two differences are that the volume type is secret instead of configMap, and that the name of the referenced secret is specified in the secretName field, whereas in a configMap volume definition the config map is specified in the name field.

NOTE

As with configMap volumes, you can set the file permissions on secret volumes with the defaultMode and mode fields. Also, you can set the optional field to true if you want the pod to start even if the referenced secret doesn’t exist. If you omit the field, the pod won’t start until you create the secret.

Given the sensitive nature of the example-com.key file, the mode field is used to set the file permissions to 0600 or rw-------. The file example-com.crt is given the default permissions.

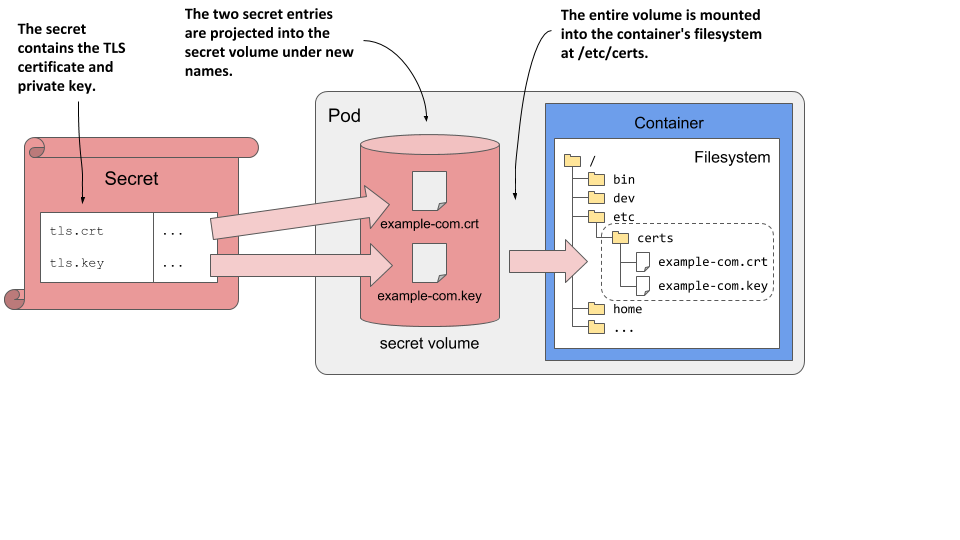

To illustrate the pod, its secret volume and the referenced secret and its entries, see the following figure.

Figure 9.6 Projecting a secret’s entries into the container’s filesystem via a secret volume

Reading the files in the secret volume

After you deploy the pod from the previous listing, you can use the following command to inspect the certificate file in the secret volume:

$ kubectl exec kiada-ssl -c envoy -- cat /etc/certs/example-com.crt

-----BEGIN CERTIFICATE-----

MIIFkzCCA3ugAwIBAgIUQhQiuFP7vEplCBG167ICGxg4q0EwDQYJKoZIhvcNAQEL

BQAwWDELMAkGA1UEBhMCWFgxFTATBgNVBAcMDERlZmF1bHQgQ2l0eTEcMBoGA1UE

...

As you can see, when you project the entries of a secret into a container via a secret volume, the projected file is not Base64-encoded. The application doesn’t need to decode the file. The same is true if the secret entries are injected into environment variables.

NOTE

The files in a secret volume are stored in an in-memory filesystem (tmpfs), so they are less likely to be compromised.

Injecting secrets into environment variables

As with config maps, you can also inject secrets into the container’s environment variables. For example, you can inject the TLS certificate into the TLS_CERT environment variable as if the certificate were stored in a config map. The following listing shows how you’d do this.

Listing 9.18 Exposing a secret’s key-value pair as an environment variable

containers:

- name: my-container

env:

- name: TLS_CERT

valueFrom:

secretKeyRef:

name: kiada-tls

key: tls.crt

This is not unlike setting the INITIAL_STATUS_MESSAGE environment variable, except that you’re now referring to a secret by using secretKeyRef instead of configMapKeyRef.

Instead of using env.valueFrom, you could also use envFrom to inject the entire secret instead of injecting its entries individually, as you did in section 9.2.3. Instead of configMapRef, you’d use the secretRef field.

Should you inject secrets into environment variables?

As you can see, injecting secrets into environment variables is no different from injecting config maps. But even if Kubernetes allows you to expose secrets in this way, it may not be the best idea, as it can pose a security risk. Applications typically output environment variables in error reports or even write them to the application log at startup, which can inadvertently expose secrets if you inject them into environment variables. Also, child processes inherit all environment variables from the parent process. So, if your application calls a third-party child process, you don’t know where your secrets end up.

TIP

Instead of injecting secrets into environment variables, project them into the container as files in a secret volume. This reduces the likelihood that the secrets will be inadvertently exposed to attackers.